Oskah Dunnin: From a Local Student to a Global Storyteller

At ANU, I’ve learned that understanding the world requires more than just theory. It’s about engaging with it, telling stories, and knowing when to listen.

Oskah Dunnin’s academic journey at ANU started in 2018 with a Bachelor of International Relations, and he quickly discovered that his intellectual curiosity didn’t fit into just one box. By 2019, he had swapped to a Bachelor of Asian Studies and a Master’s of Asian and Pacific Studies, diversifying his studies and deepening his connection to the region he had always been fascinated by.

“Asia ought to be understood on its own terms,” Oskah explains. “That doesn’t mean accepting some orientalist claim that says Asia is inherently exceptional, but it does mean we need to work harder to translate and contextualise our theoretical frameworks rather than just applying them. When you study international relations, especially in this part of the world, it’s like peeling back layers to find out not just what is happening, but why and how things are the way they are.”

Oskah’s academic growth has been marked by practical experiences too, from writing articles for The ANU Observer to taking photos for Woroni and even helping organise major student events like Big Night Out and Inward Bound. But it was a deeply personal experience in his first semester that truly shaped the course of his life and studies.

Coming into Focus

During his first semester, Oskah faced the sudden loss of a close friend to a brain aneurysm. He recalls that moment with remarkable clarity, saying, “I remember sitting in the ANU Observer office, opening the message, and realising that nothing in my life had prepared me for that moment.” While the grief was overwhelming, Oskah learned something profound: the importance of finding purpose and structure in even the most chaotic of circumstances.

In the days and months that followed, he tried to make sense of what had happened: “This was my first brush with adulthood, and as I’ve come to terms with the violence of it all, I can at least say it helped teach me something. The best advice I’ve ever heard was you need to make yourself useful at a funeral. No, it’s not about taking any spotlight – it’s about finding the order of things, and giving the world around you whatever structure you can.”

That perspective gave shape to his evolving approach to life and storytelling.

Capturing the Bigger Picture

Through his studies, Oskah focused on regional security and politics across the Asia Pacific. His internships and real-world experiences added a practical layer to his theoretical studies. A notable experience was his four-month internship with the Embassy of Ecuador, where Oskah wrote daily policy reports that documented current affairs and their impacts on Australian interests. His work there led him to interact with Ecuador’s Ambassador, who later became the country’s Minister for Foreign Affairs and Human Mobility.

But it wasn’t just the political figures and the intricacies of foreign policy that interested Oskah—it was the narratives behind them. “In politics, everything is a story,” he says. “There are protagonists, antagonists, rising tension, and conflict. The leaders we see on the global stage, like Modi or Xi, are not just politicians—they’re storytellers. Take Modi after the Gujarat riots, where he reframed violence as a story of upstanding Hindu citizens rising up against Islamic terrorists. That narrative became the foundation of his political rise. It’s the same with Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’—it’s a national story of rejuvenation under the leadership of the Party.”

Oskah’s keen interest in how narratives shape nations drives his belief that Asia’s political landscape must be understood on its own terms. “The problem with Western models of political science is that they often fail to account for the complexity of Asia. I realised early on that you can’t just apply theory to these regions—you have to adapt it to fit the cultural and historical context. Asia doesn’t always behave according to our traditional frameworks.”

This realisation came into sharper focus when Oskah enrolled in INTR2010: International Relations in the Asia-Pacific. “That was a turning point for me. I realised how different the Asia-Pacific is from the rest of the world. The course didn’t just apply theory—it contextualised and translated empirical theory to explain the region's complexity on its own terms.”

Through the Viewfinder

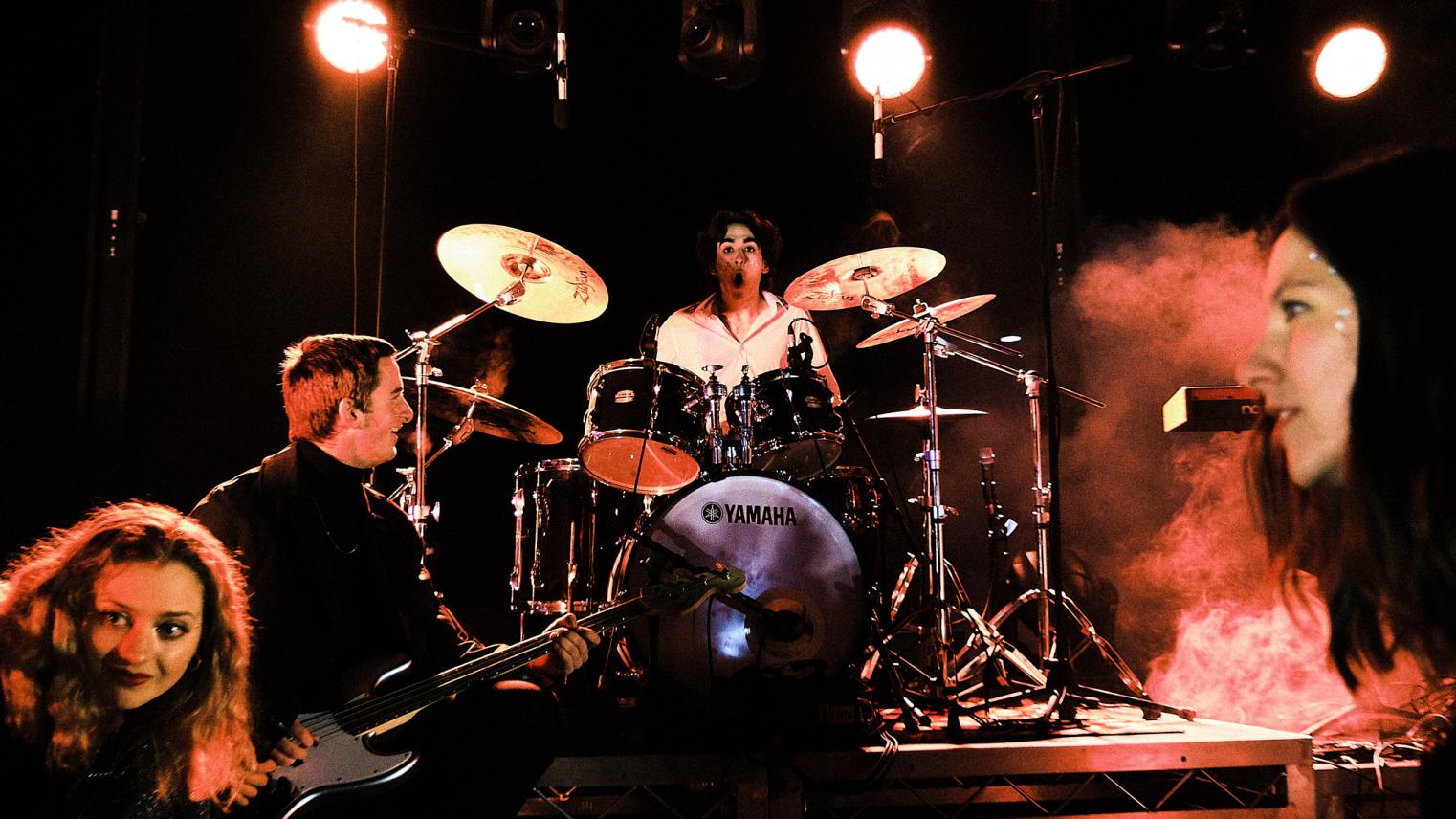

Oskah’s journey as a storyteller extends beyond politics and academia. A passionate photographer, Oskah picked up a camera a few years ago, and his work has since been featured at exhibitions in New York and even picked up by the United Nations. “Photography, for me, is about telling stories that words alone can’t capture,” he explains. “I’ve photographed Ukrainians who left their families, Indian doctors in fear for their safety, Australian journalists connecting veterans with survivors from World War II, and Iranian students hiding in fear after the Mahsa Amini protests. These stories matter because they highlight the resilience of individuals in the face of enormous odds.”

For Oskah, photography isn’t just a medium—it’s a way to understand and communicate the human experience. “I never really set out to be a photojournalist, but I guess the stories I want to tell find me, and I’m just the person who helps them get out there,” he reflects.

Asia Pacific Through The Lens

Oskah’s academic and personal growth came to life during his travels through the Asia-Pacific region, where he encountered moments that challenged and reshaped his understanding of the world. In Seoul, he arrived just days after President Yoon Suk Yeol had enacted special emergency powers that many likened to martial law. “I expected there to be palpable unrest, heightened military alert and nervous faces on the street. Instead, daily life carried on as normal, even if surrounded by stacked police barricades on most street corners, and police buses set up like mobile headquarters at major intersections.”

What stood out was how seamlessly protest blended into everyday life.

“Often these protests were elderly people sitting in plastic lawn chairs, waving the flag. Some protesters wore military fatigues, and others draped themselves in the American flag. There were even small protest gift shops hosted by Korean aunties where tourists could buy flag pins, magnets and keychains. These souvenirs often came with foreign flags too, perhaps to show solidarity with national allies like America, Ukraine, Australia, Israel and even China."

Oskah was also surprised by what he witnessed during the day of President Yoon’s impeachment. “There was no violence, and I would even be surprised if an arrest had been made that day. Around 20,000 Koreans had gathered outside at the National Assembly to call for Yoon’s impeachment, and instead of rage, they sat on freezing city roads, sang Rosé’s global hit APT, and gave speeches on stadium screens hoisted by construction equipment, all the while waving idol glow sticks above their heads. Outside the local Paris Baguette, hundreds queued up to drink free coffee donated by fellow citizens who were unable to attend the protest in person. When the politicians announced they had just impeached the President, people cheered, they hugged, danced, and shared their love for each other.”

His experience in South Korea offered an unexpected insight: “Resistance and normalcy can exist side by side. That’s not the case everywhere. In Hong Kong or India, protest feels like a rupture. In Korea, it’s part of the rhythm of life.”

Unexpected Exposures

Throughout his travels, Oskah noticed how some countries were changing rapidly, while others were evolving in subtler ways. “When I went to places like Jakarta and Singapore, the changes were noticeable but not immediately obvious. The MRT stations in Jakarta and the evolving use of the national flag in Singapore are small but significant transformations. In contrast, the changes in India and China were huge and evident in everyday life. India’s rise is marked by an emerging middle class, and in China, everything is digital. Physical currency is almost obsolete, and I barely saw cash being used.”

These experiences have profoundly shaped Oskah’s understanding of the Asia-Pacific region. “What I’ve learned is that Asia isn’t just one story. It’s a collection of evolving narratives, each unique to its context. And that’s what makes it so fascinating."

The Next Shot

As Oskah looks ahead, his journey continues to evolve. His experiences have cemented his commitment to understanding the Asia-Pacific region, and his diverse academic background—spanning international relations, Asian studies, and photography—provides him with a unique lens through which to view the world. “At ANU, I’ve learned that understanding the world requires more than just theory. It’s about engaging with it, telling stories, and being present in the moment.”

From his first semester to his international travels, Oskah Dunnin’s story is one of resilience, discovery, and a continuous quest for deeper understanding. And through his lens, both academic and photographic, he is helping to tell the world’s most important stories.

She once said, “Create something today, even if it sucks.” I still try to. This self-portrait near Shitennoji Temple in Osaka, Japan was taken with a camera Oskah had searched for in Kuala Lumpur, Bandung, and New Delhi, and finally found in Taipei, shot on a roll of film that travelled with him across Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea, and was eventually developed in Shanghai, China.

The ANU School of Culture, History and Language has partnered with CHL student Oskah to share some of the stories he captured on camera during his travels across Asia. We look forward to sharing these stories with you as part of this series. Watch this space!